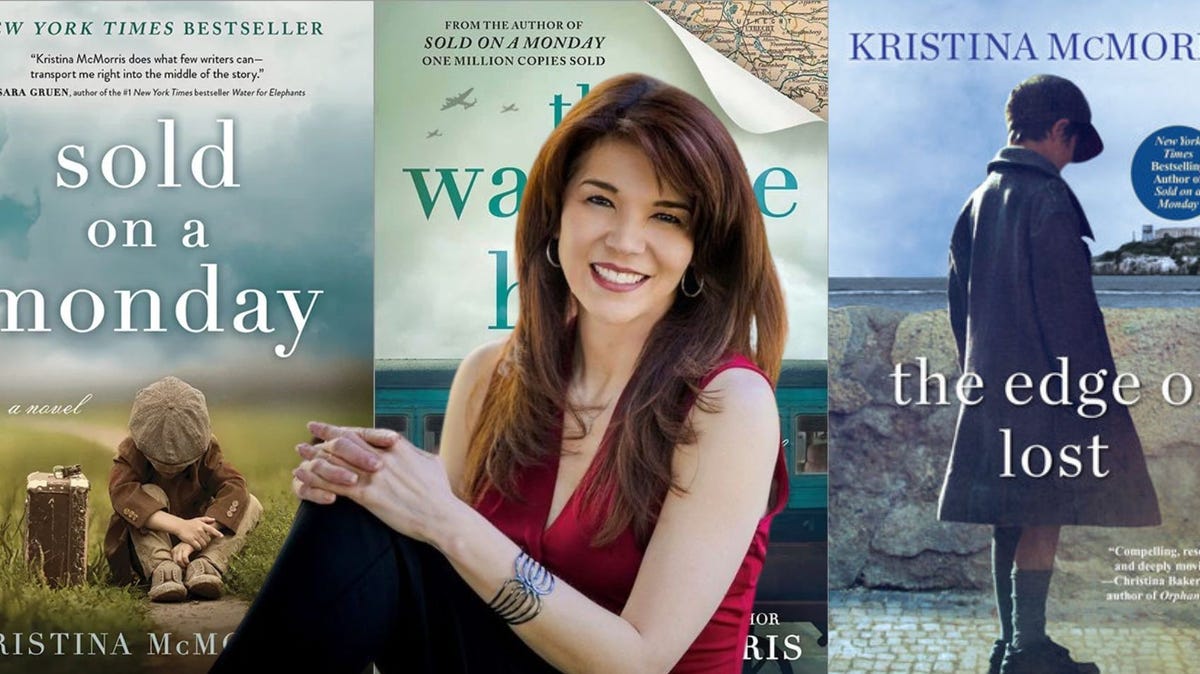

As a historical fiction author, Kristina McMorris has made a career out of exploring untold nuggets of history.

Her novel “Sold on a Monday” was inspired by a real newspaper photo of children under a sign offering them for sale. “Bridge of Scarlet Leaves” followed the non-Japanese women who voluntarily entered Japanese internment camps to stay with their spouses and children.

But it took her several decades to learn about the history right in her backyard. McMorris had heard of “being Shanghaied” as slang, but found out about the Portland Shanghai tunnels, funnily enough, from an episode of “Ghost Hunters”. Now, “The Girls of Good Fortune” (out now from Sourcebooks) connects those tunnels and the discrimination against Chinese laborers during the 1800s through its main character, Celia.

What does it mean to get ‘shanghaied’? ‘Girls of Good Fortune’ goes behind slang

In popular culture, “shanghaied” often refers to tricking or coercing someone. But the term’s historical roots refer to the method of kidnapping men to meet the growing demand for sailors in the late 19th century. The Portland Tunnels, subject to much local lore, were likely used as dungeons for “shanghaied” victims.

“Girls of Good Fortune,” set in 1888, opens as Celia awakens in one of these underground cells, drugged and disguised as a man. As she retraces her steps to understand how she got there, she begins to understand that she has been “shanghaied” and is about to be shipped off into forced labor. She’ll do anything to make it back to her young daughter, who’s been left behind in peril.

During the start of her research during the pandemic, McMorris took virtual tours of the tunnels and read historical texts from the Oregon Historical Society to fill in the blanks. It was more of a challenge than her previous novels, many of which have been set in the 20th century and relied on interviews and first-hand accounts.

That research led her to a period of intense anti-Chinese violence in the late 1800s. McMorris learned about the Tacoma Method, which refers to a mob of several hundred white men (including city leaders) violently pushing out the entire Chinese community of Tacoma, Washington in 1885. The mob intimidated families, burned churches and broke into and vandalized homes. Seen as a method to successfully push Chinese populations out, the Tacoma expulsion led to even more violence. In Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory in 1885, white miners attacked Chinese miners and set fire to their homes, killing an estimated 28 people. In Hells Canyon in 1887, 30 Chinese miners were gunned down in Oregon by a white gang.

The novel is set during this period of intense anti-Chinese sentiments, and Celia’s father is killed in these massacres.

“How have we never learned about this?” McMorris says. “Given that it is, historians will tell you, the greatest atrocity against the Chinese immigrants in America, in our history. And yet most people have never heard of it.”

As a historical fiction writer, McMorris says the best compliment she receives from readers is that her books make them want to learn more and do their own research. She sees the genre as an accessible entry point.

“That is more interesting, I hope, than a textbook from history class, when we were told just to memorize dates and names and regurgitate them for exams and it didn’t mean much to us because we didn’t humanize it,” McMorris says. “The humanizing of history, where it becomes real people that are us at a different time, they’re ordinary people during extraordinary times, in extraordinary circumstances, then we’re able to increase empathy. And I think that is really important.”

In all her work, McMorris searches for women’s roles in history that are “easily brushed over.” “When We Had Wings,” her 2022 novel with Ariel Lawhon and Susan Meissner, follows the forgotten but crucial Women’s Army Corps in World War II. She’s “endlessly fascinated” by stories of women (fictional and real) who had to disguise themselves as men for freedom, political power or to serve on the battlefield. She was also partially inspired by “Mulan,” a household family favorite, when she was writing Celia getting “shanghaied.”

Kristina McMorris’ Asian identity informs ‘Girls of Good Fortune’ characters

McMorris, who is Japanese and white, hasn’t put this much of her Asian identity into a novel since “Bridge of Scarlet Leaves” in 2012. With “Girls of Good Fortune,” she used her own experience being mixed race to craft Celia, who is white and Chinese and passing while she works as a maid for the mayor’s family.

McMorris’ father is from Kyoto, and she says he was reluctant for many years to teach her and her sister Japanese because he was “so proud of having his kids be American.” He regretted it later in his life.

“We didn’t know exactly where we fit in,” McMorris says. “Having a foot in both worlds was interesting and yet wasn’t something that we appreciated as much until we got older. And so now we absolutely love that, the feeling that we’re different in a way, that we’re unique in our own ways.”

That experience of balancing assimilation but holding onto cultural roots is something McMorris injected into her novel. And more than just grappling with her identity, Celia reckons with her privilege to pass as white and how she can use her voice to speak up for those who cannot, like her father.

“What we bring to the table is our voice, which is how we view the world, the way that we put those words together, the messages that we want to share,” McMorris says. “Most importantly, it is telling stories from history that otherwise might be forgotten. Shining a light on that in some way, I think, is absolutely important today more than ever.”

Clare Mulroy is USA TODAY’s Books Reporter, where she covers buzzy releases, chats with authors and dives into the culture of reading. Find her on Instagram, subscribe to our weekly Books newsletter or tell her what you’re reading at [email protected].

Leave a Reply