If you joined a band when you were 19, would you still be talking about it 60 years later?

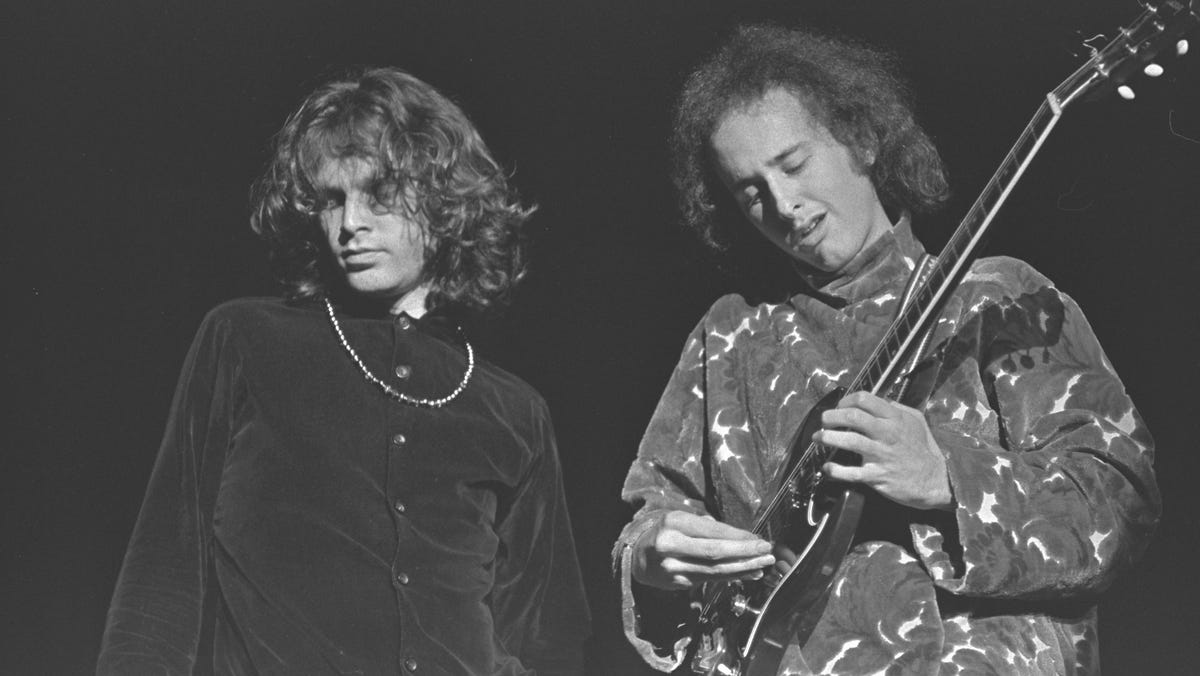

Most people would not. But this is Robby Krieger we’re talking about, guitarist for the groundbreaking Los Angeles band The Doors. So you better believe that at 79, he remains chock full of epic memories of the five years his quartet ruled the airwaves and rocked the culture.

“I think the combination of the poetry (of lead singer Jim Morrison) and the music was so different than anything else at the time, before, or maybe even now,” says Krieger, who cowrote “Light My Fire,” arguably the band’s most iconic song. “So many people come up to me at say, ‘You changed my life.’”

Those people will delight in “Night Divides the Day: The Doors Anthology” (out now from Genesis Publications, $75), a beefy new book that chronologically recounts the Doors’ rise and too-soon end after Morrison’s 1971 death in Paris at age 27.

The hardcover tome is filled with archival photos of the band and its memorabilia, along with quotes from current musicians ranging from Slash to Van Morrison as well as the group’s other members: drummer John Densmore, 80, and keyboardist Ray Manzarek (who died in 2013 at age 74).

Call it a literary time machine. One spread is a black and white photo of the band in early 1967, standing in front of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. The musicians are riding high just days after the release of their hit-packed eponymous debut album. Morrison, a magnetic if troubled front man, holds a massive stick while the rest smile at some joke.

Nearby, the caption features part of a review of the band’s show at the famous Fillmore Auditorium, where they played on a bill with the Young Rascals (“Good Lovin’”). The reviewer makes plain that The Doors were from a planet unfamiliar to that city’s flower child set.

“The Doors are a weird group,” it reads. “They start off without much and gradually get into something which is not exactly the Frisco sound but some kind of Eastern-oriented improvisation.”

The Doors magic mix? Blues, flamenco, jazz and a wild-eyed poet

For Krieger, the band made its indelible mark precisely because of its wildly different personnel. Densmore was a jazz drummer, Manzarek was steeped in Chicago blues, Morrison was a poet with a compelling set of pipes, and Krieger was a flamenco guitarist.

What could have added up to a sonic mess became solid gold, with songs such as “The End” (featured prominently in the movie “Apocalypse Now”), “Break On Through,” and “Love Me Two Times” among their many classics. The Doors were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1993.

“It was kind of meant to be,” says Krieger, who with his current band has been playing many of The Doors’ albums in their entirety at Whiskey A Go Go, the famous LA haunt where the group was the house band in the mid-’60s. “It has to be that. We were all so different, but that’s why it worked.”

The Doors indeed were an accidental miracle. Manzarek and Morrison were fellow film school students at the University of California, Los Angeles, where Krieger was an undergraduate. Densmore was a local drummer going to school a few towns away, who was brought into a group started by Manzarek that also featured his brothers.

“Then Ray’s brothers quit, so they needed a guitarist and John, who I knew, brought me in to rehearse with them and that was it,” says Krieger, who says he played that haunting slide intro to the future hit, “Moonlight Drive,” at that first gathering of the foursome. He laughs. “Jim loved that slide. He wanted me to put it on every single song. I said thanks, but no.”

Morrison and Manzarek were big book fiends and conjured the band’s name from a line in a William Blake poem: “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is: Infinite.”

The Doors’ heavy first album was a serious departure from the Summer of Love sounds pinging across the airwaves in 1967. Many songs had dark overtones, reflecting Morrison’s cerebral, if haunted, nature. None more so than “The End,” with its violent Oedipal theme. Morrison would seem to go into a trance during live renditions of the tune. Krieger says the singer was a live wire literally from the band’s formation.

“Jim was something else, man, although remember in the ’60s it wasn’t that crazy to be crazy,” he says with a laugh.

If Jim Morrison had swapped acid for meditation, one wonders ‘what might have been,’ says Robby Krieger

The guitarist says that Morrison was on acid when they recorded “The End,” and after the session was over, he snuck back into the studio and doused nonexistent flames he saw with a fire extinguisher. “Jim could ruin a show, for sure, but one thing he never was was late,” Krieger says. “He loved to create art, that’s what he was about.”

Where all four members had certainly dabbled in the various drugs of the day, Krieger says everyone except for Morrison quickly looked for an alternative mind-expansion outlet.

“We were into the Maharishi (Mahesh Yogi, spiritual guru to the Beatles), and he came to Los Angeles and we got Jim to go. He looked at (the Maharishi) from about 10 feet away and just shakes his head and says, ‘No, he doesn’t got it.’ And walked away,” he says. “I often wonder what might have been if he’d felt otherwise and given up acid and started meditating like we were doing.”

Morrison, the rebellious son of a Navy admiral, had model-ready Dionysian looks, so much so that in 1981, a decade after Morrison’s somewhat mysterious passing, Rolling Stone put him on the cover with the famous headline, “Jim Morrison: He’s Hot, He’s Sexy and He’s Dead.”

He was also a handful, Krieger says. “He’d be on acid with a bunch of people, and start turning the lights on and off really fast, just to see what would happen. Mostly, we just rolled with it. I trusted Jim, but there were times I worried he might go too far.”

“Night Divides the Day,” which takes its name from a lyric in “Break On Through,” spends a good many pages on Morrison’s most famous trespass: a 1969 gig in Miami during which Morrison, annoyed with the crowd, was arrested for indecent exposure for allegedly taking his pants down. Fiction, Krieger says.

“It was close, sure, and he would have done it had Ray not said to our equipment manager, ‘Don’t let him take his pants down!’ But no, didn’t happen,” he says.

But the damage, in essence, was done. Morrison was convicted in 1970 of indecent exposure and profanity and was awaiting sentencing when he decamped to Paris with his longtime girlfriend, Pamela Courson.

The stress of it all caused Morrison to gain weight and continue to abuse substances; his death was ruled as heart failure, even though no autopsy was performed. Morrison is buried in Paris’ fabled Père Lachaise Cemetery, where his headstone remains perpetually covered with mementos from fans.

Of the culture’s enduring fascination with Morrison and the music he and his bandmates created, Krieger seems as impressed as anyone.

“Ten years ago we had the 50th anniversary of the band getting going, and I was going, wow, 50 years and we’re still being talked about,” he says. “Now it’s 60. It just keeps going and going. It’s just crazy.”

Leave a Reply