From the bay window in our dining nook, the view down the gently sloping terrain to the road and parallel train tracks is a still one, apart from a frantic lizard hoping to avoid the watchful eyes of a roadrunner. A gust of wind stirs up a dust devil, making the yucca stalks wave. The land is dotted with colour from wild flowers and hummingbirds. This is summer in Marfa. It’s the time of year we cherish most, here in the far west of Texas.

While much of the state is dripping with humidity, our days are dry. A certain slowness is required. In animals, the search for respite is called aestivation: a period of dormancy, much like hibernation but in the warm season. We humans, meanwhile, cultivate indoor spaces to become cool, calm shelters from the sun during the day; we nurture outdoor alcoves to allow us to be outside as it rises and sets. After all, according to Joan Didion, writing from California’s Death Valley, “stories travel at night on the desert”. These regions, which make up a third of the Earth’s land, might seem inhospitable — but for those who learn to live with them, they can be magical.

We — two arts writers and photographers, who met while studying in Austin and were drawn back to Texas after living in Denmark, Germany, Mexico and Cuba — decided to find others who, like us, welcome the heat. We visited the Patagonian Steppe, Mars-like swaths in Jordan, the India-Pakistan border and the south-western US. The result — our book Desert by Design — is an ode to these arid landscapes and the creative minds who inhabit them. These are difficult places to live, and over thousands of years a number of architectural tricks have been developed to live in them comfortably; the people we meet have put them to use with style and innovation.

As temperatures rise globally, “we are going to have to look to homes in regions like these to understand how future generations are going to live”, says Demion Clinco. A Democrat who served in the Arizona House of Representatives, he is also chief executive of the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation and counts a 1970s residence designed by Judith Chafee as part of his property portfolio.

The American architect, who married a modernist style with a reverence for nature, had immersed herself in the 4-acre site near the Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona, learning the patterns of the sun and the shade. The result is a network of interconnected rooms that twist around courtyards and patios of varying shape and size, keeping the Sonoran Desert in view without letting it become overwhelmed by sun and heat.

Partially submerged into the earth, the lower levels stay cool with opposing windows that encourage a cross-breeze. It is precisely this attunement to the local landscape and climate that is its enduring strength, says Clinco; the question for future architects is not just how to live with heat, but how to do so while minimising reliance on air conditioning.

Nadia Begin, a resident of the experimental eco-city Arcosanti, in Arizona, agrees; architecture should not fight its surroundings, but be adapted to it — and that goes for the residents too. Arcosanti might have imposing concrete structures with sci-fi geometries and huge circular windows, but they are built into the hillside; the walls were cast in the ground’s silt so that the texture and tone match. “We constantly have to develop more sustainable systems, which means that we have to learn to effectively engage with [the environment] around us,” she says. “Isn’t that what the world needs more of?”

Begin and her husband adopt low-tech cooling tactics such as lime-washing windows to filter the light. “We are intentionally not isolated from the desert,” she says. The late Italian-American architect Paolo Soleri, who began designing Arcosanti in 1970, “consciously wanted us not to get too comfortable. We should feel cold in winter and warm in summer. We shouldn’t be in a bubble.”

Soleri had studied under Frank Lloyd Wright, and though the two had differing visions, they both believed in organic architecture that harmonises with its surroundings, that takes inspiration from vernacular construction, but reinterprets it in modern materials.

Other architects embrace tried and tested elements just as they are. When Karl Fournier and Olivier Marty, of Studio KO, and their mentor Jean-Noël Schoeffer acquired an old farmhouse 33 kilometres from their Moroccan base, they renovated it as a retreat to suit their modern needs. But they did so, Fournier says, by “creating with as little impact as possible”, maintaining the traditional insulating thick walls, small windows, network of small rooms and low doorways that all work to regulate temperature.

Johnny Ortiz-Concha, a chef based in a secluded northern New Mexico village, and his partner, curator Maida Branch, are some of the many people we spoke to who are sanguine about the heat, accepting that living in a desert simply means you will be hot. They live in a traditional earthen home, where they eschew air conditioning and central heating (it can get cold here, too). “Experiencing discomfort is part of existing in the natural world,” Branch says. “It’s where growth happens.”

For the couple, the summer heat makes the nights here, and their daily margarita, all the more satisfying. Ortiz-Concha forages rose hips, plums, pine shoots and prickly pear from the surrounding area for his supper club. “Desert plants are harder to get to and tend to produce less [fruit],” he says. “But they’re so much sweeter because they have to fight to survive.”

These environments are far from barren; many are their own small oases amid the sand and rock. In Egypt, near the Libyan border, the home shared by designer-architect India Mahdavi and her friend, environmentalist Mounir Neamatalla, is surrounded by a verdant grove of palm trees.

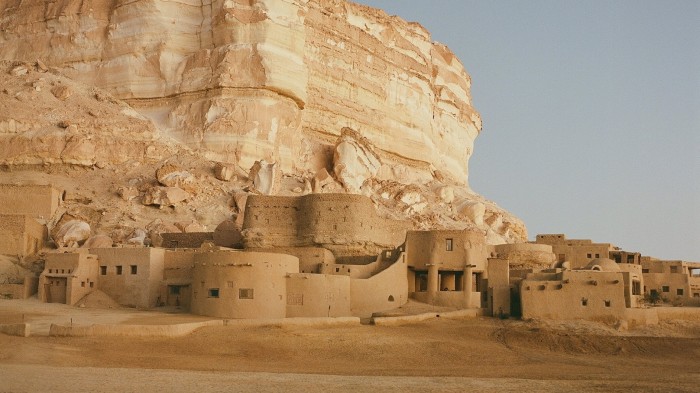

Positioned between the salt lakes of Siwa with the dunes of the Sahara beyond, and the western slope of Adrére Amellal (the “White Mountain” that lent its name to Neamatalla’s eco-hotel), the sandy pink house blends into the environment. Small windows minimise the heat. A number of areas for sitting and dining are open to the outdoors — capitalising on cool breezes and the shade as they shift throughout the day. One circular dining space has tall walls but no ceiling; the perfect spot for stargazing. The compound is more than a den for midday hibernation; it is built in concert with the desert.

Eight hundred kilometres east, in the cacophonous desert metropolis of Cairo, the art scholar and traditional costume collector Shahira Mehrez has also created her own lush enclave in the sky. Collaborating with sustainable architect Hassan Fathy, she modelled her penthouse apartment on the layout of traditional homes where “no space is lost”, with latticework window coverings and a sunken marble bathtub.

She refers to darker, more intimate corners, like her bedroom, as “cocoons” and says she spends the majority of her time in the courtyard, with its plants, central fountain and pink plaster walls. Here, adobe bricks stacked in triangular formations filter daylight while allowing a draft to flow through. “It is a house for all seasons,” Mehrez says triumphantly.

Fournier, Marty and Schoeffer used Berber techniques and natural insulating materials such as mud, chalk, palm and eucalyptus in Marrakech, while Mahdavi and Neamatalla’s thick walls are made from the local Egyptian material known as kershef, a blend of mud, rock salt and other minerals, which means the building melds with its surroundings.

In a micro-desert in the Otago province, New Zealand, Veronica Alkema and Gary Stewart also turned to the ground, utilising rammed earth for thick walls that regulate temperatures in their modern, angular house. “Actively engaging with a place, being connected to the way things change season to season, understanding the cycle of nature, has been great for our mental balance,” says Alkema.

But others have a more radical interpretation of traditional methods. In the high altitudes of southern Colorado, artist Ronald Rael engages with the earthen buildings of his ancestral homeland by restoring existing adobe structures and creating contemporary ones with technologies such as 3D printing.

“I feel like I grew up in the 1800s, when electricity and running water were brand new,” Rael says of his rural upbringing. “And now I work with robots in the very same place.” His mud-based buildings and sculptural installations are at once familiar — inspired by indigenous tradition and “the genius of the past” — and completely futuristic.

Meanwhile, in the Indian state of Rajasthan, Dushyant Bansal and Priyanka Sharma of Studio Raw Material opted for another bountiful natural resource: marble. Both studied at London’s Royal College of Art but were drawn back to their home country by the stone. From centuries-old quarries, the duo harvested a patchwork of castoffs to pave their long central hallway, which connects to spacious rooms with sparse furniture and high ceilings. They show that what is often seen as a barren and inhospitable land can provide great treasures.

It may be like an oven out there, hot enough to fry an egg on the pavement, but in these dry, dusty locales, incomparable beauty, a trove of generational knowledge and a wealth of resources can be found, for those who pay attention. To live stylishly and sustainably, the best solutions are often right under your feet.

“Desert by Design”, by Molly Mandell and James Burke (Abrams)

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ft_houseandhome on Instagram

Leave a Reply