‘Vanderpump Hotel’ is coming to the Las Vegas Strip

Get ready for more glamour and luxury in Las Vegas as Lisa Vanderpump, the queen of reality TV and entrepreneur, is diving into the hotel business.

Cheddar

Brittany Cartwright is on the way to Santa Barbara, California, for a weekend in the sunshine.

She’s relaxed and chatting with friends in the backseat of their shared car. Then comes the ding of a text notification.

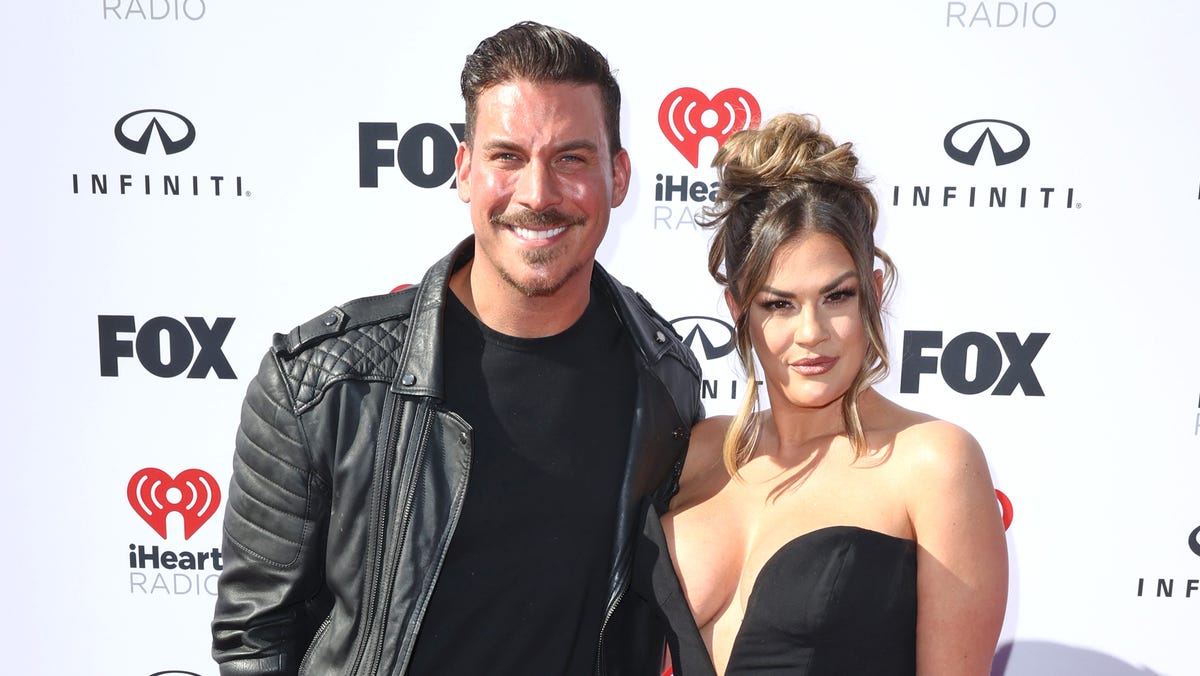

“He’s already starting to text,” she says, unlocking her phone to see a note sent by husband Jax Taylor, who is at a rehab facility.

The scene in Episode 3 of Season 2 of “The Valley,” a spinoff of reality Bravo’s “Vanderpump Rules,” highlights how people with alleged anger issues can continue to harm loved ones using digital platforms, even while receiving professional help. The scene depicts a kind of emotional injury that occurs outside the context of physical and/or sexual violence, and its verbal and psychological nature can be much more difficult to prove as a serious type of hurt.

Taylor, who is in therapy nearly seven hours a day at the time of episode three, “rage checks in on me” during 15-minute breaks amid his therapy sessions, Cartwright says in the episode. The deluge of messages inquire about her activities, interactions with others and relationship with him, she says in a confessional interview.

“I actually thought that whenever he was in there for 30 days that I would be able to have some kind of peace,” she says in the episode. “How dumb was I?”

“This is a time of calm where things feel peaceful, maybe even better than before,” Jordan Pickell, a relationship expert and trauma counselor based in Vancouver, Canada, says of the scene. “But as a therapist, we start to track that the tension is building, then there will be an incident, then there will be reconciliation and then it will be calm again.”

‘It’s a huge first step to start therapy’

The Season 2 premiere begins with the couple separated, Cartwright weighing a reconciliation as she co-parents their son from a rental home. But when Taylor allegedly flipped a coffee table after seeing a video Cartwright sent another man, “that completely changed everything,” she said in the premiere earlier this month.

That Taylor spent 30 days in an in-patient facility last year should not be overlooked, Pickell says. It’s a very hopeful sign that someone is getting help. But people with emotional dysregulation can also use therapy to mask their behaviors, she says.

“It’s a huge first step to start therapy,” says Pickell. “In some cases, therapy can be used as a way to shield or win arguments. I’ve seen people on the receiving end of that behavior and they describe their partners weaponizing the fact ‘they’re working on themselves’ to deflect from the impact they’re still having.”

Even though Taylor is not physically present with Cartwright, his persistent messages serve as a venue of emotional pressure. For her, this means little to no reprieve.

‘The Valley’ friend group is accountable, too

“The Valley” also shows how a friend group can be held accountable for harmful relationships, too. Some of the men in the friend group continue to text Taylor or attend his promotional events. While on the surface that may seen innocuous, it’s important for any friend group to pay attention to one another, Pickell says.

“The behavior that is showing outside of the relationship is likely the tip of the iceberg,” she says. But it’s up to the friend group to declare “zero tolerance” very clearly for emotionally distressing behavior. This could look like calling out someone or even taking the extreme measure of cutting them out of the group.

Even if someone isn’t flipping furniture, unwanted, ongoing digital contact can still be a threat, Pickell says. This is never the recipients’ fault, she adds. But there are ways to recognize it and take action. Resources such as itsnotviolent.com feature an interactive text “game” that teaches users how to see and respond to potentially harmful online dialogue.

“If someone in your life is still harming you, even while they’re in therapy, you are allowed to set boundaries,” Pickell says. “You’re allowed to say, ‘I support you, I’m glad you’re going to therapy, but you can’t be contacting me at this time.’”

What to do if you receive emotionally distressing texts

- Notice how you feel in the conversation. Disengage if you’re feeling unsafe, Pickell says. Giving answers could further feed their attacks.

- Minimize the person’s online access to you. Block them and remove digital connections with them.

- Go to a support network. Be honest about what’s going on with a friend or family member, Pickell says.

- Consider counseling. Therapy is equally important for recipients of emotional harm, Pickell says. “These folks can be really logical,” she says, and an expert can help unravel their justifications and design boundaries that make sense.

Leave a Reply