Watch trailer for Netflix’s ‘Oklahoma City Bombing: American Terror’

Netflix’s documentary ‘Oklahoma City Bombing: American Terror’ arrives on the 30th anniversary of the tragedy. See the exclusive trailer.

On the morning of April 19, 1995, an Army veteran once described as “probably the best soldier” in his company parked a commercial truck carrying a 4,800-pound bomb in downtown Oklahoma City. Timothy McVeigh targeted the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building because of the numerous federal agencies scattered among the structure’s nine stories, where hundreds worked.

The date marked two years since the fatal end of a 51-day standoff between law enforcement and cult leader David Koresh in Waco, Texas. In retaliation, McVeigh rented a truck using a fake I.D. made with a clothing iron to transport the fertilizer bomb that he and his friend Terry Nichols assembled. The two first met in the Army, and later bonded over their anti-government views. At 9:02 a.m., the explosive detonated, obliterating one-third of the building, which also housed a daycare center.

Thirty years after the shocking act of domestic terror that claimed 168 lives, the tragedy is the focus of new projects: NatGeo’s three-part docuseries “Oklahoma City Bombing: One Day in America” is streaming on Disney+ and Hulu. And Netflix’s “Oklahoma City Bombing: American Terror” 1 hour, 24-minute documentary chronicles the day of the bombing, featuring interviews with people on site and law enforcement officers desperate to solve the case. The documentary also spotlights local residents’ resiliency and ability to step up for their grief-stricken community.

The inspiring Oklahomans who ‘found a heroic piece of themselves’

Director Greg Tillman tells USA TODAY that while making his film, he found a consistent theme: “In spite of the horror that they’re all experiencing,” he says, “so many people in that moment found a heroic piece of themselves that they may never have known about until something like this happened in their life.”

The filmmaker applauds the “hundreds” who “ran right to the site to see if they could help people.” Those attempting to save survivors in the building did so with the understanding that they were risking their own lives. Dr. Carl Spengler, who performed onsite triage, remembers in the documentary a surgeon who, when he “crawled into the hole to do (an) amputation he handed his wallet back and said, ‘If this collapses, give that to my wife.’”

Tillman says FBI officials told him as he made the documentary they were mindful about requests for donations, “because anything they asked for from the public, they got 20 times more than needed.”

Timothy McVeigh in custody for another crime during hunt for bomber

Charlie Hanger, then an Oklahoma Highway Patrol trooper, pulled over McVeigh shortly after the bombing. McVeigh’s getaway car, a 1977 Mercury Marquis, didn’t have a license plate. McVeigh threatened Hanger with the loaded gun bulging from his jacket, so Hanger arrested McVeigh and brought him to Noble County Jail in Perry, about an hour north of Oklahoma City. There, McVeigh was booked and saw on TV the extent of the devastation. Because of a court backlog, McVeigh remained jailed, though authorities had not yet connected him to the bombing.

Meanwhile, a blown-off piece of McVeigh’s truck led authorities to a rental reservation, which resulted in a sketch that ultimately connected him to the crime. The FBI searched a database to see if anyone named Timothy McVeigh had been arrested and discovered he’d been apprehended in Perry. On April 21, the FBI phoned Hanger, who informed them that McVeigh was currently in court “35, 45 minutes away from walking out the door.”

When asked about the coincidence Mark Gibson, then assistant district attorney for Noble County, reasoned with a Southern drawl, “God was watching us.”

McVeigh was executed in 2001. His co-conspirator Nichols is serving a life sentence in Florence, Colorado.

A dedicated doctor, grieving mother and transformed survivor

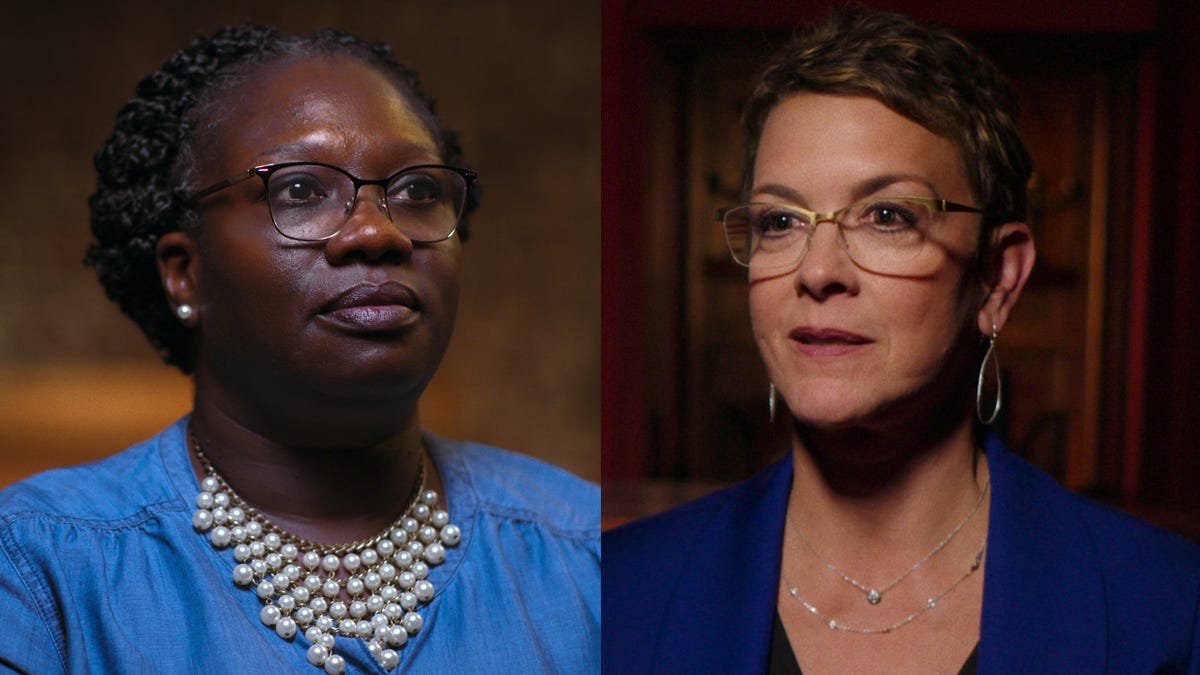

The documentary depicts the experiences of three people irrevocably touched by the tragedy that will stay with viewers long after the documentary ends.

Spengler, a third-year medical resident, accepted a friend’s invitation for breakfast near the Federal Building after his shift ended at 7 a.m. Spengler says after the bombing he “took off running” to the scene and provided triage care. He determined which victims needed the most urgent attention and which could not be saved. “And to compound all of that, you had children,” Spengler emphasizes.

Renee Moore worked near the building and relied on its daycare for her 6-month-old son Antonio Cooper Jr., who was among those killed. She recalls nights where she would drive to McVeigh’s prison and “just sit out there in the dark, wondering how I could get in so I could hurt him.” In an interesting twist of fate she welcomed another son, Carlos Moore, on Antonio’s birthday.

Amy Downs, an employee of the building’s Federal Employees Credit Union, regained consciousness beneath a mountain of debris. Rescuers located Downs but had to flee before they could free her from the rubble after authorities thought they had found a second bomb.

“They were leaving me buried alive,” Downs remembers. “And I’d start thinking about my life and relationships and doing something with your life to help others, and I’d never been a mom. And all of a sudden, it was just so clear. I didn’t live a life true to myself. Once free, Downs vowed to God, “I would never live my life the same.” She became a triathlete, earned her MBA, became CEO of the credit union, an author and a motivational speaker.

Leave a Reply